Alexander (Alessandro) MOISSI was born in Trieste on April 2, 1879 when the city was in Austria-Hungary (now it’s in Italy). He was baptized in the St. Nicolo dei Greci Greek Orthodox Church and was the youngest of the five children of the Albanian businessman Konstantin Moissi (Moisiu in Albanian) and his wife Amalia, neé de Radio (from an Albanian-Italian family).

Around 1900 Alexander MOISSI was just one of the nameless extras at the Vienna Burgtheater – with no prospect of making a serious career, but he was able to make that leap in Berlin.

When Max REINHARDT opened his illustrious small theater in Berlin with Ibsen’s Ghosts, MOISSI was cast as »Oswald«, a morbid character that made him a stage star. He followed that with a further success as the suicidal »Fedor Protasov« in Tolstoy’s play The Living Corpse.

MOISSI won artistic fame on REINHARDT’s Berlin stages, but in Antisemitic Vienna he was suspected of being a Jew:

I believe that Moissi is derived from Moises.

Kikeriki, Viennese Satire Newspaper, August 17, 1913, p. 3

Moisés is the Spanish version of Moses, so for educated Antisemites this was a clear indication of the ancestry of the stage star.

But in Vienna the rumors got even worse when MOISSI married his colleague Johanna »Terwin« (her legal name was Winter) in Berlin on December 16, 1919.

The witnesses to their marriage were Friedrich Brehmer (a former frigate captain from the Imperial Navy) and Sophia Liebknecht. Sophia Liebknecht was the widow of the recently murdered anti-military and communist revolutionary Karl Liebknecht.

It was his name and not that of the German frigate captain that attracted the most attention, especially in right wing circles in Vienna, so rumors targeted MOISSI as a Communist as well as a Jew (two things that often merged in the imaginations of Antisemites who coined the phrase Judeo-Bolshevism to bring them together).

On June 19, 1920, half a year after the Berlin wedding, the New Viennese Stage presented a guest performance with Alexander MOISSI and a garden party in his honor. It ended in a riot: German nationalist students, wearing their fraternity colors, swinging clubs and cheering, wanted to beat up MOISSI and the »Communists« and »Jews« in attendance. MOISSI wasn’t injured because the outnumbered guests were able to fight off the band of attackers.

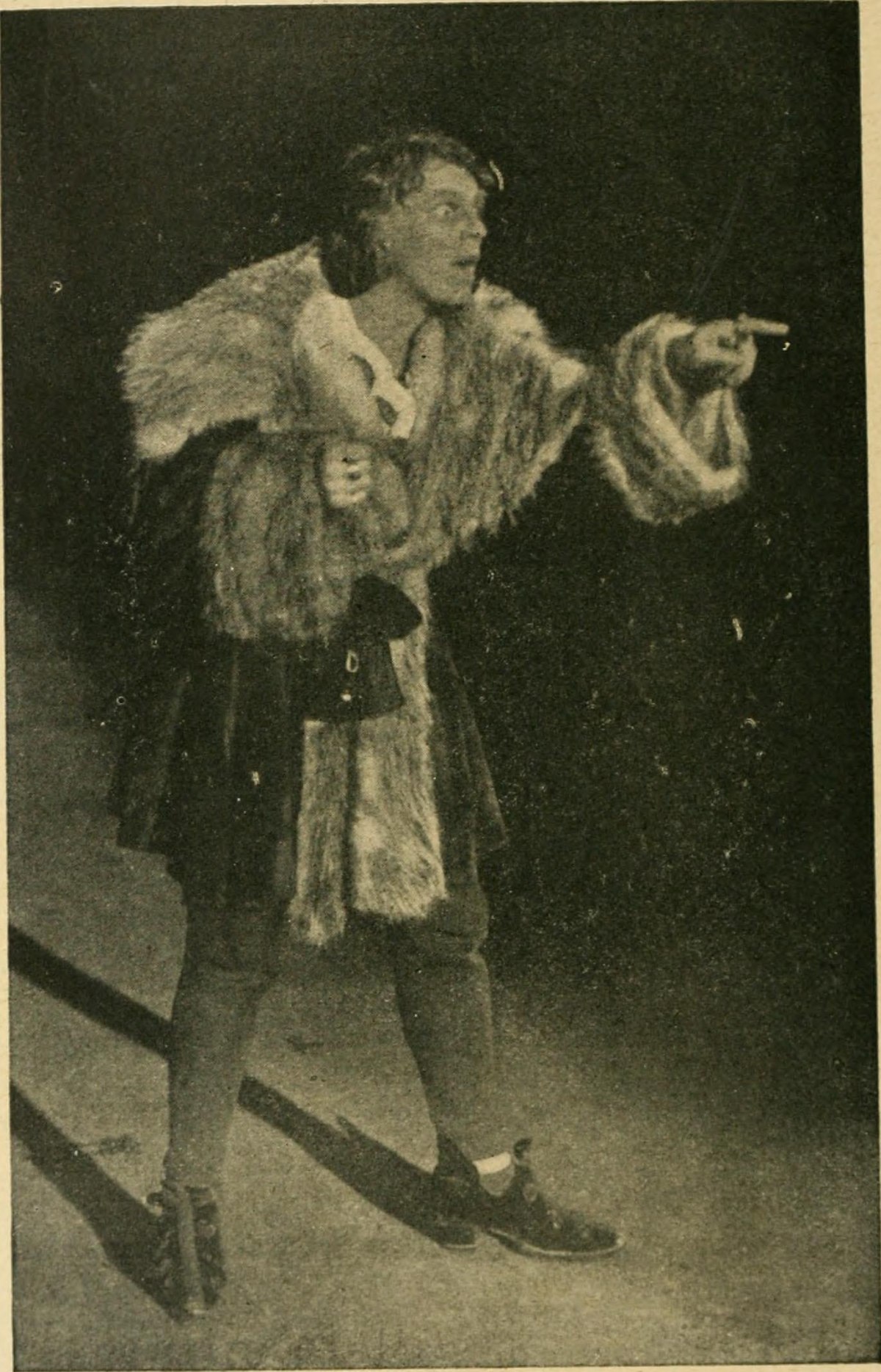

On August 22, 1920, two months after the turbulent Vienna guest performance, the two MOISSIs made their first appearance in a Salzburg Jedermann.

Johanna Terwin played the role of »Buhlschaft«, while her husband Alexander MOISSI played the title role of »the rich sinner« who discovered his true faith at the end and was saved through the mercy of God – performed in Max REINHARDT’s original staging in front of the baroque facade of the cathedral, on the top of which a figure rises: »Salvator Mundi«, Christ as Redeemer or Savior of the World.

At first the weather refused to cooperate and dark clouds covered the sky, but when MOISSI began to declaim the »Lord’s Prayer« – it is said to come from Jesus, and didn’t appear in text for the play by the poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal – the cathedral facade was bathed from the gable down in the light of the setting sun. The audience, including the archbishop, is said to have been moved to tears.

In the year of peace 1920, a year and a half after the end of the First World War and the Spanish Flu pandemic – the deadliest epidemic of the 20th century – poverty and hunger were still widespread in Salzburg so a play about the death of a rich man wasn’t everyone’s cup of tea:

Certainly, every proletarian who reads the mystery play, with its maudlin story of Everyman’s happiness and ending with his repentance and death, will have to decisively reject the morality of the drama: this sort of morality and its reward could only be applauded by the rich bourgeoisie.

Salzburger Wacht, August 22, 1920, p. 2

The Social Democratic Workers’ Party of Salzburg was nevertheless grateful for a special presentation for invalids, widows and orphans.

However, there was a lack of international audiences because Europe had closed its borders and the European train route of the pre-war years from Paris to Constantinople via Strasbourg, Munich, Salzburg, Vienna and Budapest had long since been cut The Simplon-Orient-Express luxury train that had been reactivated after the end of the war, made a large detour south of the defeated Central European countries.

That meant that the addresses of the elite of Vienna society published in the last High-Life-Almanac of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy were now far away from the new European train route.

The legendary founding of the Salzburg Festival with its illustrious audiences took place in this bleak context. The Austrian social elite listed in the High-Life-Almanac – Andrian, Billiter, Billroth, Hofmannsthal, Kestranek, Morawitz, Petschek, Sgalitzer, Sobotka, Wassing and Wittgenstein – continued to take their summer vacations in the scenic paradise of the Alpine lakes and mountains even after the end of the Monarchy.

So, instead of international luxury trains the audiences mainly relied on regional and local rail routes for their arrival and return journeys: the Kaiserin-Elisabeth-Bahn RR, the Tauernbahn RR, the Salzkammergutbahn RR (the narrow-gauge railway from Bad Ischl in Upper Austria to Salzburg via St. Gilgen), and the electric tram in the city of Salzburg.

Throughout his life the Shoah survivor Dr. George W. Sgalitzer from Seattle, (doctor, pianist, and member of the Honorary Board Salzburg Festival Society) remembered MOISSI in the brilliant title role in front of the facade of the Salzburg Cathedral.

Jedermann had a contrary impact on the poet Hermann Bahr, who lived in Salzburg: »the flood of Hebrews that Jedermann brought to our unfortunate city« drove him to flee to Berchtesgaden.

He felt very differently about the Greater Germany Conference of Nazis (with Adolf Hitler in attendance) that took place in Salzburg that year, and also about the first appearance of summer-vacation-Antisemitism in August 1920 when the nearby town of Mattsee proudly declared itself to be »Jew free« – as was reported on August 8, 1920 in the Christian-Social Salzburger Chronik.

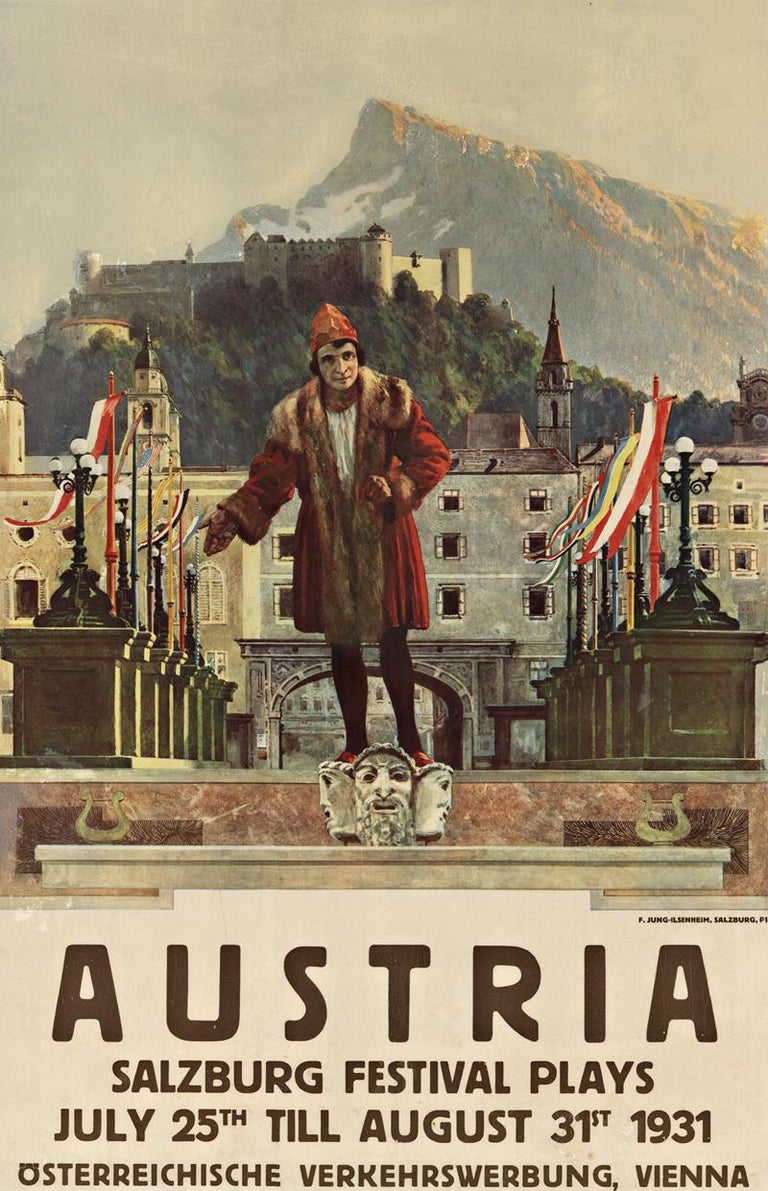

As historical studies have clearly shown the Festival was widely denigrated as »Jewified« in Antisemitic Salzburg. On August 30, 1931, MOISSI, loved by some, hated by others, made his last appearance as Everyman.

At the end of this festival summer, MOISSI was still the celebrated star guest in the »Dream Night at Schloss Leopoldskron« staged by Max REINHARDT. Berta Zuckerkandl-Szeps, who ran a literary salon in Vienna, reported this with fascination on August 29, 1931 in the »Neues Wiener Journal«.

On the other hand, it is hardly known that MOISSI was good friends with Friderike and Stefan ZWEIG and liked to spend time at their house at number 5 Kapuzinerberg – »Villa Europa« – rehearsing his roles in the garden and using the typewriter in the study.

MOISSI was then working on his »women’s novel« (still untitled). It was a literary project that only a few connoisseurs knew about: his wife Johanna Terwin, the ZWEIG couple and Dr. Ernst Karajan (father of the conductor Herbert von Karajan).

As director of the Salzburg State Hospital it was Dr. Karajan who had to give his consent so that MOISSI could attend a delivery in so he could describe it accurately in his novel. MOISSI’s appearance in the hospital as »Dr. Alexander« failed to remain secret because he was so well known that he was easily recognized despite being dressed as a hospital doctor.

When the story became public the Salzburg Nazi party took notice and used the »Dr. Alexander« affair for their September 1931 election campaign. Their racist publications denounced it in the most vile terms:

The Jew Moissi enjoyed himself!

An outrageous load of filth! Moissi-Moses as an obstetrician!

The delivery of a Christian woman as spectacle for the Jews!

The well-known stereotype: an innocent Christian woman as a victim, a Jew as a perpetrator. MOISSI was treated as a Jew without actually being one.

Racism had reached the middle of society. This was made crystal clear when his wife Johanna Moissi-Terwin sought to defend him publicly by stating that her husband was »of purely Aryan descent« and cited his baptismal certificate from Trieste as evidence. Her published defense letter was addressed specifically »To the women of Salzburg!« (Salzburger Volksblatt, October 2, 1931, p. 5f).

MOISSI’s presence also stirred up public passions in Vienna while he continued to perform there. For example, when he played the suicidal »Fedor Protasov« in Tolstoy’s play The Living Corpse at the Raimund-Theater the building was surrounded by police to prevent a mob of Antisemites from getting in and disrupting the performance – a success that generated the headline:

Peaceful run of Moissi-performance.

Neues Wiener Journal, February 1, 1932, p. 5

On the occasion of the Vienna guest performance, MOISSI commented on the background of the agitation sparked by the Salzburg Nazis:

… and I have more than the suspicion that it does not apply to me alone, but that – as amazing as this sounds at first moment – with me also Max Reinhardt is to be hit.

There are Salzburg circles, which Reinhardt’s activity is a thorn in the eye for a long time, admittedly one does not dare to insult him directly. So now he shall get something on the detour about me.

Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, February 3, 1932, p. 3

It is also noteworthy that MOISSI refused the Salzburg Festival’s request to announce he was quitting his role as Everyman. He was unwilling to surrender to the Nazis. The Salzburg Festival removed him anyway on the grounds that it did not want to expose itself to the dangers of public demonstrations.

The Antisemitic satire magazine Kikeriki promptly rejoiced when it was announced that MOISSI was no longer allowed to play Everyman in Salzburg:

Everyman can play it now, just no Jew!

Kikeriki, May 7, 1932, p. 4

The Salzburg Festival opted for the German actor Paul Hartmann, who played Everyman in 1932, 1933 and 1934, then became a »state actor« in Nazi Germany, and finally president of the Nazi’s Reichstheaterkammer – their national organization for theaters and actors that banned Jews from acting on stages or in films.

In his World of Yesterday, Stefan ZWEIG recalled an ending for the life of stage star Alexander MOISSI – in a world premiere of the drama Non si sa come (Nobody knows how) by Nobel laureate Luigi Pirandello in Stefan ZWEIG’s German translation that would be performed in the Vienna City Theater with MOISSI in the leading role.

But it ended otherwise. Stefan ZWEIG was in Vienna in the spring of 1935 when he read in a newspaper that MOISSI was seriously ill. Two days later, ZWEIG was standing in front of his friend’s coffin.

Alexander MOISSI died from pneumonia at the age of 55 on March 22, 1935 in a sanatorium in Vienna. He had forbidden that funeral speeches be given when he was cremated in the Vienna crematorium. But it is reported that Arnold ROSÉ and Bruno WALTER played Beethoven’s Adagio.

MOISSI’s grave is located in the Morcote cemetery in the Swiss canton of Ticino, near his last home.

Sources

- Archive of the Salzburg Festival

- Vienna City and State archives

- Salzburg City and State archives

- ANNO – Austrian Newspapers Online

- Austrian Theater Museum in Vienna (Moissi collection: birth certificate)

- Berlin Municipal Marriage Register (Alessandro Moissi and Johanna Winter, both identified as Roman Catholics)

- Mödling St. Othmar Catholic Parish Register of Deaths (Amalia Moissi)

Translation: Stan Nadel

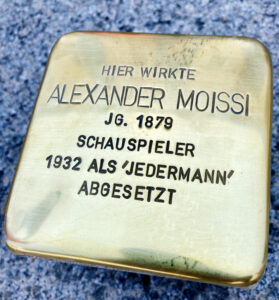

Stumbling Stone

Laid 17.08.2020 at Salzburg, Max-Reinhardt-Platz

Alexander Moissi as Jedermann

Alexander Moissi as JedermannSource: Archive of the Salzburg Festival

Alexander Moissi as Jedermann

Alexander Moissi as JedermannSource: Archive of the Salzburg Festival, Photo Ellinger

Alexander Moissi as an international figurehead of the festival city of Salzburg (1931)

Alexander Moissi as an international figurehead of the festival city of Salzburg (1931)

Alexander Moissi’s grave in the cemetery of Morcote Switzerland (Canton Tessin)

Alexander Moissi’s grave in the cemetery of Morcote Switzerland (Canton Tessin)Source: Wikipedia

Relocation of the Salzburg Festival, August 17, 2020 (Max-Reinhardt-Platz): Gert Kerschbaumer, Helga Rabl-Stadler, Danielle Spera, Hanna Feingold

Relocation of the Salzburg Festival, August 17, 2020 (Max-Reinhardt-Platz): Gert Kerschbaumer, Helga Rabl-Stadler, Danielle Spera, Hanna FeingoldPhoto: Salzburger Festspiele/Lukas Pilz