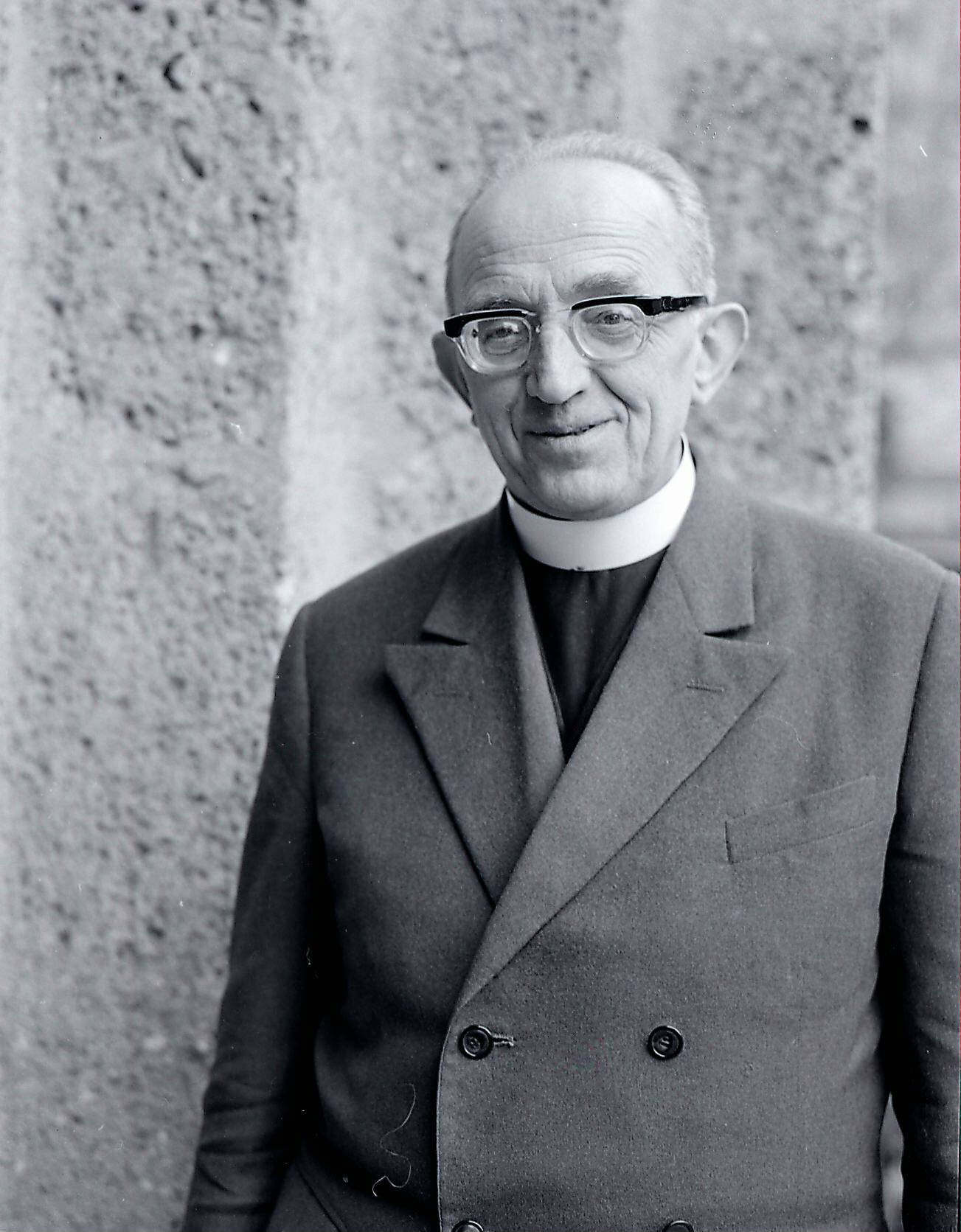

Franz ZEISS was born in Altenmarkt (in the State of Salzburg’s Pongau district) on November 7, 1892. Baptized Catholic he attended the archbishop’s boys’ school »Borromäum« in Salzburg and the seminary for the priesthood.

On Trinity Sunday 1915 he was consecrated as a priest in the Salzburg cathedral and after that he worked in the city of Salzburg as religion teacher, chaplain of the Catholic journeymen’s association and pastor. After 1934 he served as the pastor of the St. Andrä parish.

Franz WESENAUER was born in Ebensee (in Upper Austria’ Gmunden district) on June 8, 1904. He too was baptized Catholic and attended the archbishop’s boys’ school »Borromäum« in Salzburg and the seminary for the priesthood.

He was consecrated as a priest in 1930 and at first he worked as curate in the Wörgl parish in Tirol which was part of the Salzburg archdiocese. Under the Nazi-Regime he became curate in the St. Andrä parish where he served as youth pastor and supervisor of the seminarians.

The St. Andrä parish headquarters was in the church on the Mirabellplatz that gave the Andrä Quarter its name. The severe destruction associated with the air raids near the end of the Second World War that hit the Andrä Quarter and its distinctive church remains vivid in the collective memory of the older generation.

In contrast, the lifesaving assistance of the two priests ZEISS and WESENAUER, along with the reliable families that helped them, has been forgotten – even though (or perhaps because) they were among the few in Salzburg who could be counted among the »righteous«.1

During Nazi rule the Roman Catholic Church in the Nazi district »Gau« Salzburg was confronted with the aggressive anti-clericalism of »Gauleiter« [Gau leader] and »Reichsstatthalter« [Reich Governor] Dr. Friedrich Rainer.

After the start of the war Rainer also served as Reich Defense Commissioner for War District XVIII. In that function he gave the police instructions on March 11, 1940 to search all parish offices for the army postal addresses of soldiers from War District XVIII (the collection of these addresses for sending religious tracts was prohibited on grounds of national »defense«).

But when they made their surprise raids Gestapo found that their secret operation was no surprise to the parish officers. They had been warned ahead of time by someone at police headquarters, a devout Catholic named Maximilian Klimitsch.

He and his wife had confided in their pastor Franz ZEISS and he had passed the information on to the parish officers. Pastor ZEISS and the Klimitschs were arrested by the Gestapo in March 1940. Police Sergeant Klimitsch was sentenced to ten years imprisonment by the »Supreme SS and Police Tribunal« in Munich and he died in an SS penal unit in September 1944.

His wife Angela was sent to the Aichach prison, where she survived the terror years.

Pastor Franz ZEISS was arrested by the Gestapo on March 13, 1940 and he was transferred from the police jail to the State Court jail in February 1941. On July 12, 1941 the »Supreme SS and Police Tribunal« in Munich sentenced him to ten months imprisonment for failure to report an unauthorized release of secret material — his crime was that he had failed to denounce the Klimitsch couple for informing him about the secret police operation.

The sentence had been exceeded by the 16 months he spent in investigative custody so the pastor was released (though he remained under police observation from the on, as was documented by the notation »Pol. Liste« [Gestapo list] on his card in the police registration files. It is only against this background that we can properly appreciate his civic courage and humanity.

After his release from jail Pastor ZEISS faced another challenge. A Catholic convert from Judaism, Franz Leo Breuer (born in 1916) had been forced in 1938 to abandon his law studies in Vienna because of his Jewish origins and was due to be deported to a concentration camp in April 1942.

He managed to escape from a Viennese collection center and was able to survive the terror years hidden – as a »submarine« – in Salzburg thanks to the help of Pastor ZEISS. In 1975, three decades after the liberation, ZEISS recalled:

… although it meant risking my neck, I had to take care of him. At first the operator of the small inn »Zur Schranne« took him in and cared for him without a [ration] card. To avoid attracting attention Breuer alternated between Salzburg and Bad Ischl, where he could hide temporarily with a well-known lady.

Ischl was chosen because the narrow gauge RR that ran there at the time made many stops and was where it was easier to avoid being discovered by a military patrol.

Later Breuer stayed in a more rural area around Grafing and Ebersberg in Bavaria. But then he came back to Salzburg again and found refuge with a woman in Salzburg-Itzling. My parish nurse at St. Andrä in Salzburg at the time, Dr. Sieglinde Rödleitner, helped provide him with food and such like.

He was nearly discovered by a commission set up as a result of the bombing damage to find habitable quarters. But in the end he was able to get through to the end of the war. By then his nerves were completely shot.

Franz Leo Breuer was able to complete his studies after the liberation of Austria. To give thanks for his rescue he had a votive tablet placed in the Lourdes chapel of the Capuchin church in Salzburg with an inscription that reads »Maria hat geholfen [Mary helped] – Dr. Breuer Franz 1945«.

He was not the only one that Pastor ZEISS was able to help — as an interview revealed. He was able to conceal the »ancestry« of some individuals who were in danger because under the Nuremburg Racial Laws they would have been counted as »Full Jews« or »Mongrels« if the authorities found out the truth about their backgrounds.

This lifesaving assistance was possible because as a matter of law before the Nazis took over Austria in 1938 all births, baptisms, marriages and deaths were recorded by the parish priests in registration books kept in the parish offices. These parish registers also recorded all conversions by Jews to Catholicism.

All this information took on a life and death political significance when the Nazi regime pursued its racial politics and charged the parish offices with providing parish register excerpts demonstrating non-Jewish ancestry to the authorities responsible for issuing the so-called »Aryan certificates« that were so important for survival in Nazi Germany.

An examination of the police registration files indicates that the Nazi authorities sometimes remained unaware of the Jewish background of some individuals as the »ancestry« entries on their registration cards failed to indicate the »full Jew« or »1st degree mongrel« designations which would have been noted had the authorities known their true backgrounds.

It is noteworthy that Olga ZWEIG, a Salzburg resident who was the cousin of the author Stefan ZWEIG, was baptized by von Franz ZEISS in the St. Andrä parish church on July 4, 1942.

At that time Olga ZWEIG (whose father was Jewish and whose mother was a Catholic with no Jewish roots) was already listed in the police registration files as a »full Jew« (with the compulsory first name »Sara«) — a deliberate falsification at the behest of the Gestapo.

Despite this Olga ZWEIG survived the terror years — and thanks to her care and discretion so did her handicapped baptized Catholic foster son Rudi whose Jewish »ancestry« remained completely unknown to the Gestapo. Olga ZWEIG and her foster son lived on the first floor of 6 Linzer Gasse until 1964.

Olga ZWEIG’s friend, the widow Franziska HAMMER, lived on the 2nd floor of the same house. She remained close to the priests ZEISS and WESENAUER through all the political turbulences of the times and helped with their lifesaving work.

Franz WESENAUER, curate of the St. Andrä parish and later boarding school director2 and Pastor of St. Elisabeth’s, recalled later:

Sometime around 1940/41 an unknown woman came to us in the vicarage [of St. Andrä] with a blond boy of about thirteen who, although Catholic, was completely Jewish by ancestry. She asked for our help as his parents had already disappeared.

I was faced with the question of either rescuing this boy or allowing him to be killed. I couldn’t hide him myself as the Gestapo were constantly going in and out.

So at first I brought him to a family named Hammer in the Linzer Gasse.

After Christmas – the woman had come to me shortly before Christmas – I went around to some farmers asking if one of them couldn’t hide the boy. None had the courage to do so. First the baker Schmidhuber in Anthering took him in.

He was already caring for some seminary students [who had been expelled from Salzburg after the Nazi regime had closed the Borromäum boarding school and seminary] so his presence wouldn’t attract attention.The lad, nicknamed Jussi, lived there for two or three years. People took him for a student and he went to church so he wasn’t noticed. In the end all the others had gone home and only Jussi was left. Towards the end of the war a rumor suddenly spread asking what was really going on with this boy. This was around the fall of 1944.

To save him from the threatening danger I secretly brought him to another place in Upper Austria. As far as I know he was also in the Mattsee Abby for a short while. At the end of the war he went through the Russian lines and finally rode to Vienna on a tank.

After the liberation of Austria »Jussi« visited Salzburg once to thank those who had helped him flee and who had saved him at the risk of being persecuted themselves and possibly loosing their own lives. The rescuers didn’t make a fuss about their lifesaving activities.

They realized that those they had saved, mostly converted or baptized »Jews« [that is individuals who were Christians in their own eyes and those of the Christian churches, but who were still Jews according to the Nazis and other racial Antisemites], generally wanted to keep their backgrounds hidden given the continued Antisemitism of many Austrians.

We should also note that thanks to the initiative of Pastor Franz WESENAUER St. Elisabeth’s became Austria’s first »Pax Christi Church« devoted to peace and reconciliation.

It was also where the first Austrian inter-religious gathering of Christians and Jews took place. A relief called »Jewish Passion« by the sculptor Yrsa von Leistner was installed in the St. Elisabeth Peace Church to commemorate that event in 1972.

After the liberation, Franz ZEISS and Franz WESENAUER were recognized as »victims in the struggle for a free and democratic Austria«. Later both priests were also awarded the honorary title of prelate and they died in 1991.

Their graves can be found in the cemetery behind St. Peter’s Church in Salzburg’s Old City.

1 Erika Weinzierl: Zu wenig Gerechte: Österreicher und Judenverfolgung 1938-1945 [Too little Justice: Austrians and the persecution of the Jews, 1938-1945], Graz, Wien and Cologne, 1969, 4th edition 1997.

2 One of the pupils in the boarding school in Salzburg’s Andrä Quarter that Franz WESENAUER directed after the liberation in 1945 was Thomas Bernhard, who later became one of the most important literary figures in Austria (see: Die Ursache, Salzburg 1975 – translated and included in: Gathering Evidence, New York 1986).

Sources

- Archive of the Salzburg Archdiocese

- Salzburg city and state archives

- Widerstand und Verfolgung in Salzburg [Resistance and Persecution in Salzburg], vol. 2, p 470 ff (Interview with Franz ZEISS and Franz Wesenauer by Günter Fellner)

Translation: Stan Nadel

Stumbling Stone

Laid 14.07.2015 at Salzburg, Mirabellplatz 5 (Kirche St. Andrä)