Mathias HORVATH was a construction worker of Hungarian origin who lived with his family in Slovakian Petržalka near Bratislava.

From November 1940 on he worked for the Railway Construction branch of the German Railways in Salzburg that quartered its foreign workers mainly in barracks near the Hauptbahnhof [main railroad station] and along the Bahnhofstraße – sleeping quarters near their workplaces.

Mathias HORVATH, who was arrested by the Gestapo on February 13, 1941, was one of the first railroaders to be persecuted for political reasons in Salzburg.

But for a long time his violent death remained unknown because he was neither an activist with the organized resistance nor a Salzburger. He was killed in the Mauthausen concentration camp on January 29, 1944.

The smashing of the organized resistance along the rail lines of the Salzburg region by the Gestapo at the beginning of 1942 is far better documented.

Around 100 railroaders associated with the Communist and socialist resistance groups were prosecuted and at least 29 of them were killed, from A to W (Franz ASCHENBERGER to Engelbert WEISS). It is also notable that in order to choke off all organized resistance forever the Gestapo deported nine of their wives to Auschwitz via the German Railways in 1942, including the leader of the Communist women’s cell Anna REINDL.

That gave the Nazi regime a free hand to increase its exploitation of workers in the service of its war of extermination and to engage in police terror against insubordinates among the forced (i.e. slave) laborers who replaced the millions of domestic workers who were engaged in military service or who had been arrested for resistance.

Flight, refusing to work, disobeying orders, and resistance were all grounds for punishment, but in cases involving forced laborers the witnesses and victims’ compensation records that we find for other victims are rarely available so we know little about them.

In the surviving documents from their persecutors the terror victims, whose voices were silenced, are often blamed for their own fate — as in the example of Josef Kosciolek. Born in Cracow on January 17, 1899, this married Catholic machinist was conscripted for forced labor on the German Railways in Salzburg where he died at age 44 – place of death: Salzburg Gestapo headquarters at what was then 5 Hofstallgasse (now it is the Franziskanergasse) in the expropriated Franciscan Monastery.

Dr. Hubert Hueber’s Gestapo report just says:

The Polish civilian worker Kosciolek Josef was found hanged in the holding cell of the local office at 4pm on 11/23/43.

There is no explanation of how the prisoner in the »holding cell«, a small cell used for short term detentions, was able to hang himself without the assistance of a rope and hook murder is more likely.

The Gestapo alone – without any police or judicial doctor’s involvement – certified the cause of death as an »apparent suicide«.

Two days later the body was buried in the city cemetery, presumably in an anonymous grave in the »tomb of the forgotten« or »poor sinners’ corner«.

The whole incident was completely hidden from the public.

We know that as an »essential war industry« the German Railways recruited labor from all the Nazis’ conquered and exploited countries — including both »civilian workers« and prisoners of war who were conscripted for forced labor.

Research on the life histories of foreign workers in the railway camps of Salzburg is hampered by the fact that they were rarely included in the police registration files that provide so much information about the lives of other victims. Forced laborers were just recorded on long lists: there are more than 30 such double-sided hand written lists labeled »railway construction – 8 Bahnhofstraße«.

These consist of handwritten lists of foreigners’ personal information that are often hard to decipher and/or questionable transcriptions from the Cyrillic alphabet into the then current German cursive. They list personal and family names, date and place of birth, religion, marital status, citizenship, occupation, date of entry and departure, and miscellaneous remarks.

These lists indicate that French prisoners of war were »granted leaves of absence« by the German military in order to get around the prohibition against forcing POWs to work – as in the example of Paul Baffogue, a POW from »Stalag VII A« in Moosburg on the Isar, who was assigned to the German Railways construction camp in Salzburg.

Baffogue was one of the many forced laborers who fled from the camp to return home after their homelands were liberated.

Was it a successful escape?

Because of the lack of documentation we still don’t know. Some made several attempts to escape, like the seven Czech »civilian workers« who, having been caught twice made a third attempt in August 1942.

Did they finally succeed, or were they caught and deported to a concentration camp? Again, we don’t know. Women fled too, like the 20 year old French woman Louise Pernay who »eloped« to Paris in September 1943 after several months of forced labor in Salzburg.

We can hope that she experienced the liberation of her Parisian birthplace in August 1944, but can’t be certain.

Terse comments like »flight«, »arrest«, or »Gestapo« are written next to the names of more than 80 women and men from about twelve countries — without any indication of what befell them afterwards. It is known that not all of them survived the war years.

Iwan Juchtarow is one example. Born in Gorki Russia (Nizhni Novgorod before 1932 and after 1990) on January 28, 1922, he lived in the Ukrainian city of Poltava before he was dragged off to Germany and registered in the Salzburg railway construction camp on September 2, 1943.

On December 29, 1943 he was removed from the list with the remark »Gestapo«, presumably held in police custody for an undetermined period of time before he was reinstated as a track worker in the railway camp on March 30, 1944.

There is no indication of any further arrest and deportation on the list, but research has uncovered the fact that the 22 year old Iwan Juchtarow was deported to the Dachau concentration camp as »Russian protective custody prisoner« number 92502 on August 20, 1944.

He was transferred to the Flossenbürg concentration camp on September 3, 1944 and on April 2, 1945, three weeks before the camp was liberated by US troops, he was murdered there.

When a name on the Railway lists is marked with a small cross instead of the remark »flight«, «arrest«, or »Gestapo« the worst has to be assumed: death in Salzburg.

But not all the deaths of victims whose names are marked with crosses can be reconstructed and verified with documents. And it is also the case that official causes of death have sometimes been falsified in order to conceal inhuman living and working conditions – as the results of difficult research has demonstrated for six lives that were cut short:

• Miroslav KOLAR was born in Olomouc, Czechoslovakia (which became part of the German ruled »Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia« in March 1939) on August 11, 1922. He was only 19 years old when he began working as an electrician’s assistant in the German Railways camp on the Bahnhofstraße on March 27, 1942 – the very day when he was killed by »electric current«, his first work day in Salzburg (burial place unknown).

• Luigi COBAI was born in Tarcento (in the Friulian Italian province of Udine) on September 26, 1898.

He was Catholic, married (supposedly with five children) and a skilled bricklayer. Just when he began working in the Railways camp is unclear.

The only thing documented is that this 43 year old Italian »civilian worker« was reported dead in Salzburg on July 16, 1942 and »committed suicide by cutting his throat« was the official cause of death (burial place unknown).

• Eugène VADON was born in the small French village of Saint-Victor-sur-Rhins (Loire Département) on October 9. 1921.

He was an unmarried Catholic laborer who was sent to Salzburg from Vichy, the capital of the unoccupied part of France administered by the regime of Marshall Philippe Pétain. He was housed in the German Railways camp on the Bahnhofstraße while he worked in the Gnigl marshalling yards.

On May 8, 1943 the 21 year old was working in the marshalling yards when he was reportedly crushed to death by a locomotive (burial place unknown).

• Wladyslaw Jan KOWAL was the son of Polish Catholic parents and was born in Cattenstedt (Saxony-Anhalt, Germany) on August 7, 1913.

At some point during or after the First World War his parents took him back to Poland. He was married with a child and lived with his family in Cracow, which was the headquarters of the German run General Governorate portion of conquered Poland.

On July 30, 1943 he was just a few days short of his 30th birthday and only 16 days into his work assignment in Salzburg when he died from a bullet from a 7.65 caliber pistol.

The official cause of death was »suicide by a shot in the head«, but how would a recently arrived foreign »civilian worker« for the German Railways have gained access to a pistol? (Burial place unknown).

• Latif ČELIKOVIĆ was born in Ripač Yugoslavia (in Bosnia-Herzegovina, near what is now the Croatian border) on November 12, 1902. He was a married Muslim laborer who had two children.

He lived with his family in the Yugoslavian capitol Belgrade, a city that had been badly damaged in the 1941 German attack that culminated in a German occupation.

The 41 year old Muslim was registered in the German Railways camp on the Bahnhofstraße as a »Serbian civilian worker« and on the night of March 3, 1944 he was run over by a train at the Salzburg Hauptbahnhof [main railway station] (burial place unknown).

• Klawdia (Claudia) SOLOMACHA, née Schulika, was born in Obuchowka (or Obuchowska, which may now be called Obukhiv — in what was then the Ukrainian region of the Russian Empire) on December 30, 1913 and was an Eastern Orthodox Christian (patriarchate unknown).

She was married (number of children, if any, unknown) and since 1934 she had lived in the Ukrainian town of Gubinicha/Hubynycha [two different transliterations of the same Cyrillic name] near Dnepropetrovsk before she and her husband Filip were forced to go to work in Germany.

On November 10, 1943 she was registered in the German Railways camp at 8 Bahnhofstraße as an »eastern worker«, one of those who had to wear »OST« [meaning east] written in large letters on their clothing. On December 20, 1943, ten days before her 30th birthday and her 40th day working in Salzburg, she was killed at the Gnigl marshalling yards when a train cut off both of her legs in a work accident — according to the official report. (Her burial place is unknown).

The list of workers at the German Railways camp indicates that her widowed husband Filip Solomache returned to the Ukraine, which is not verifiable.

Towards the end of the war the German Railways camp where Mathias HORVATH had been arrested in February 1941 became a death trap. The strategically important railway yards where the barracks were located were the main target of American air raids against Salzburg, but foreign workers were denied access to the air raid shelters in the city’s hills —even though it was mostly foreign workers who had built the shelters.

At least five foreign workers were killed at the Hauptbahnhof [main railway station] in the first air raid against Salzburg on October 16, 1944 — and their bodies were recovered by a contingent of foreign forced laborers. Two of those killed can be minimally identified:

• Jean Baptiste CHADEBAUD, who was born in Ivry-sur-Seine near Paris (Département Val-de-Marne) on November 8, 1905; and

• Stefan KULKA, who was born in Jarocin, Poland on December 13, 1890.

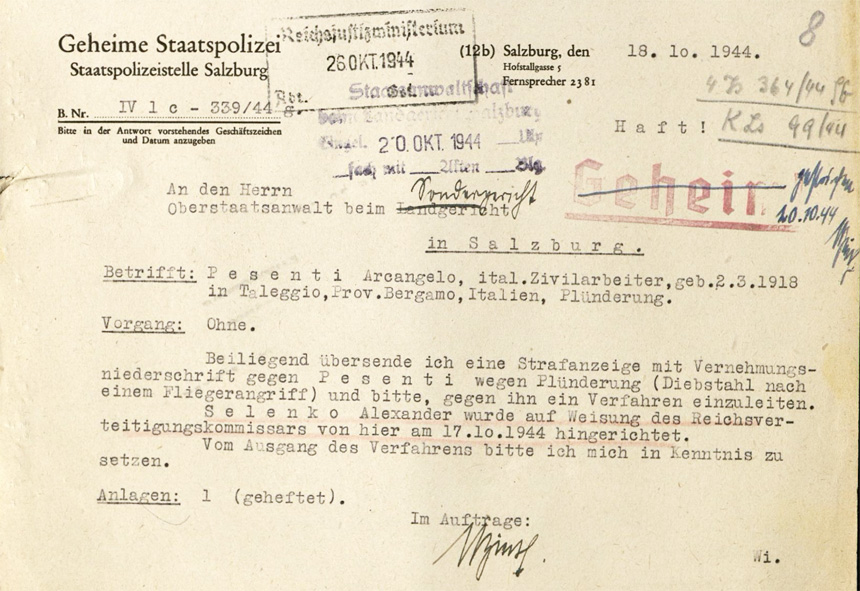

A Russian POW and an Italian »civilian worker« (who was an ex-POW) fell victim to the Nazi terror when they were allegedly seen »attempting to appropriate« two packages of 100 cigarettes each during the clean-up of the bombed out camp barracks.

Under the Nazi regime this constituted »plundering« – though we should remember that since 1939 it was the territories occupied by Nazi Germany that had been plundered and it was these very same POWs and »eastern workers« whose labor the Nazis had plundered and exploited.

The Russian POW in Salzburg who a supervisor had accused of plundering was hanged by the Gestapo in front of his fellow workers to serve as an example on October 17, 1944.

The 33 year old terror victim was Alexander ZIELONKA (or SELENKO), born on December 26, 1913 in Naliboki (near Minsk in White Russia — now Belarus).

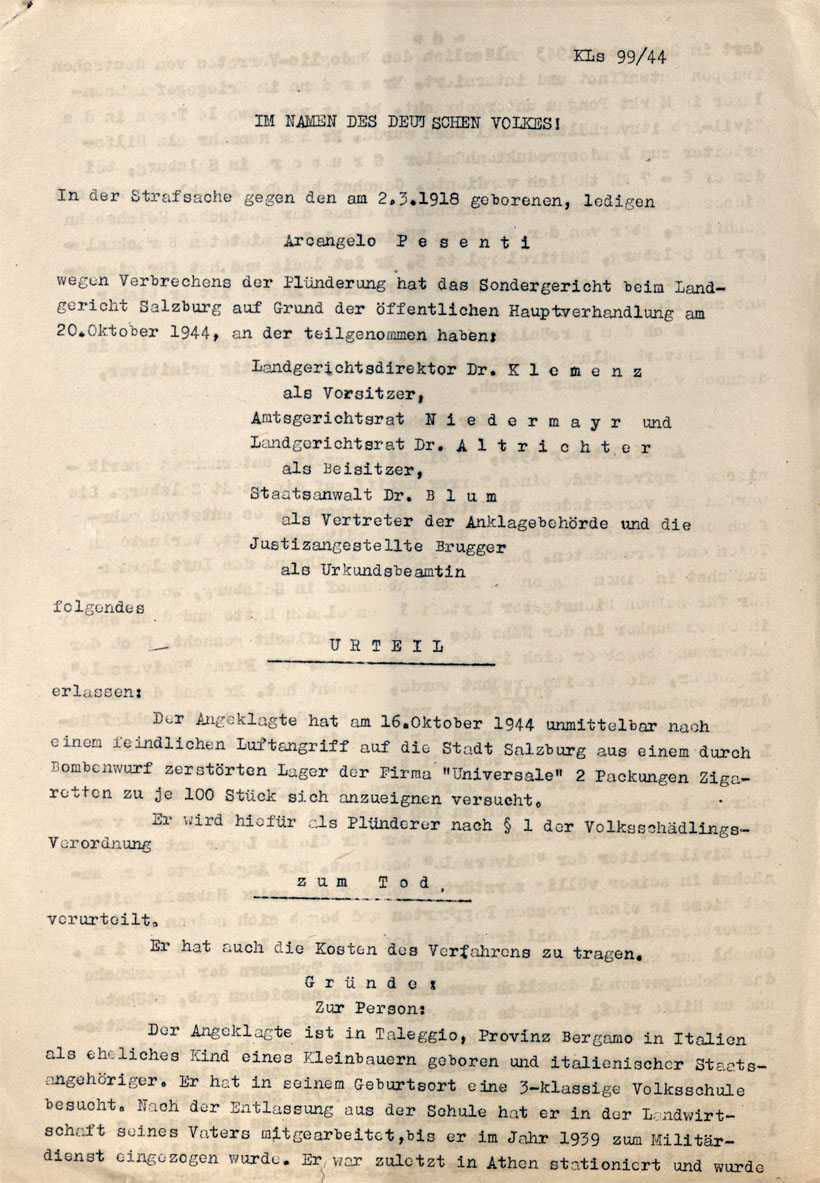

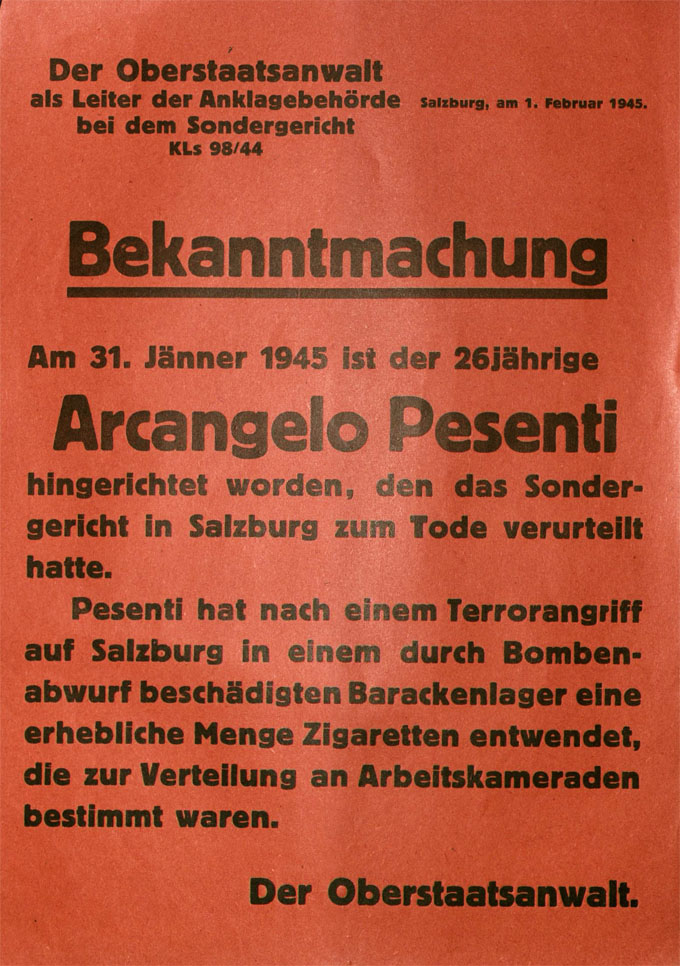

Three days later, on October 20, 1944, the Italian »civilian worker« Arcangelo PESENTI was brought before the court in Salzburg and as an example to deter others he was convicted in an expedited process.

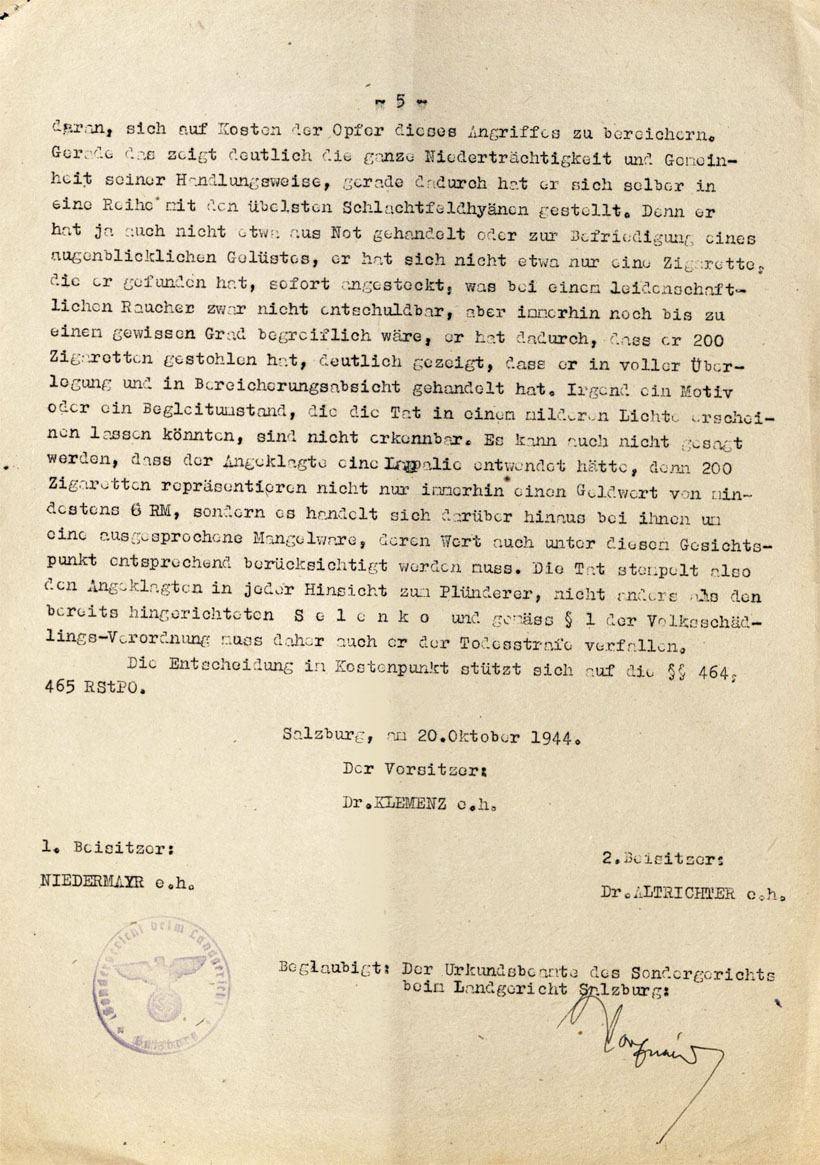

During the process of the Salzburg »special court« it was noted that on the instructions of the Reich Defense Commissioner (Dr. Gustav Adolf Scheel, Gauleiter [regional governor] for Salzburg) the Russian POW Alexander SELENKO had been executed by the Gestapo for the same crime on October 17, 1944.

After that the »special court« couldn’t pass any other sentence than the death penalty. Arcangelo PESENTI, who vainly maintained his innocence – he said he hadn’t any possibility to have gotten the cigarettes that were supposedly going to be given to him – was sentenced to death by the Salzburg »special court« for violating § 1 of the German »People’s pest ordinance« of September 5, 1939.

PESENTI’s appeal was rejected on December 15, 1944 and even the request for mercy by the Italian Consul in Munich was unsucessful.

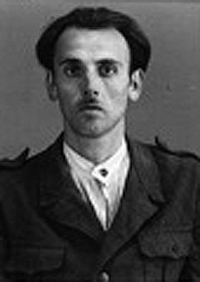

The court files also contain personal information so we know that Arcangelo PESENTI was born in Taleggio Italy near Bergamo on March 2, 1918.

He was an unmarried Catholic farm worker who had been in the Italian army who had served in Greece when Italy had been an ally of Nazi Germany.

After the Italian surrender to the allies he was fortunate enough to have ended up in an German POW camp rather than being murdered by his former allies (which was the fate of thousands of Italian soldiers in Greece and the Aegean islands).

He had been incarcerated in »Stalag XVIII C« in St. Johann im Pongau (about 65 Km south of Salzburg) since September of 1943, but he became a »civilian worker« for the German Railways in Salzburg on October 5, 1944.

On January 31, 1945 the 26 year old Arcangelo PESENTI was guillotined in the Munich-Stadelheim prison – which led the Munich chief prosecutor to inform the Salzburg State Court succinctly that

»the affair was concluded without incident«.

Sources

- Salzburg city and state archives

- Criminal records of the Salzburg Special Court (KLs 99/1944)

AGAINST FORGETTING

A musical performance in the context of laying »Stumbling Blocks« near Salzburg’s main Railway Station on January 27, 2015.

In rememberance of people murdered by the Nazis and against forgetting the innumerable atrocities of the Nazi regime. Composition and recording by Gerhard Laber.

© 2015 by Gerhard Laber. (Reproduction only allowed with the permission of the composer)

In solidrity with the victims, Gerhard Laber

Translation: Stan Nadel

Stumbling Stone

Laid 27.01.2015 at Salzburg, Salzburg Hauptbahnhof/Südtirolerplatz

Arcangelo Pesenti

Arcangelo PesentiPhoto: State Archive Munich

Criminal complaint of the Gestapo Salzburg against Arcangelo Pesenti

Criminal complaint of the Gestapo Salzburg against Arcangelo PesentiSource: Salzburger Landesarchiv

Death sentence of the Salzburg Special Court against Arcangelo Pesentii

Death sentence of the Salzburg Special Court against Arcangelo PesentiiSource: Salzburger Landesarchiv

Death sentence of the Salzburg Special Court against Arcangelo Pesentii

Death sentence of the Salzburg Special Court against Arcangelo PesentiiSource: Salzburger Landesarchiv

Pillory poster of the chief public prosecutor of Salzburg

Pillory poster of the chief public prosecutor of SalzburgSource: Salzburger Landesarchiv

The symbol of the Nazis' civil and military courts: A sword and scales of justice combined with the Nazi Party eagle and swastika

The symbol of the Nazis' civil and military courts: A sword and scales of justice combined with the Nazi Party eagle and swastika

Photo: Gert Kerschbaumer

Photo: Gert Kerschbaumer