Hilde (Hildegard) SCHMIDBERGER was born in Salzburg on November 1, 1925 and baptized Catholic. She was the younger child of an unmarried woman who worked as a servant and office assistant in Salzburg.

At the beginning of the 1930s her mother moved away from Salzburg, but left her young daughter behind. Hilde’s married father, a hairdresser, continued to live in Salzburg with his family even after the Nazis took over in 1938.

Hilde grew up in various institutions under the supervision of the Child Welfare Office and graduated successfully from a secondary school. But as an illegitimate girl from the lower classes she was not allowed to learn a trade.

Hilde worked as a housemaid in St. Gilgen on the Wolfgangsee (28 km east of Salzburg), and later in the State Hospital in Salzburg. Hilde was already known to the authorities because she had once been held for a week under juvenile arrest for theft.

Hilde was considered a problem child, as the Juvenile Court under that Nazi regime put it – surprisingly with a great deal of understanding:

As a mitigating circumstance the girl may be credited with the fact that she had a very neglectful education and experienced little love in her youth, so that the joyless existence of her youth made it easier for her to fall into the wrong direction compared to someone who had enjoyed a loving upbringing.

When the court put in this good word for 19 year old Hilde on November 29, 1944 she was still a minor, but she was old enough to be liable for punishment and had been in police custody since November 21st.

On November 23rd Hilde SCHMIDBERGER was charged with theft of a traditional Salzburg jacket, a traditional hat and a suitcase full of clothing – all in all worth 230 Reichsmarks, in accordance with § 460 of the Austrian criminal code of 1852 (still in effect under the Nazis) – »petty larceny«:

All thefts which are not to be punished as crimes according to the provisions of Sections 172 to 176 shall be punished as minor transgressions by simple or severe detentions from one week to six weeks, but the confinement may be exacerbated by the circumstances.

In a normal case the 19 year old would have just gotten a jail sentence and not the severest possible sentence: a death penalty in an expedited process. But it was the timing, not the nature of the deed that doomed her: theft after the first American bombing attack on Salzburg in 1944.

This enabled the Austrian chief prosecutor Dr. Stephan Balthasar to charge her before the Salzburg »Special Court« on November 29, 1944 with a crime carrying the death penalty:

I charge you [Hilde SCHMIDBERGER], as an enemy of the People, with having committed robbery and plundering.

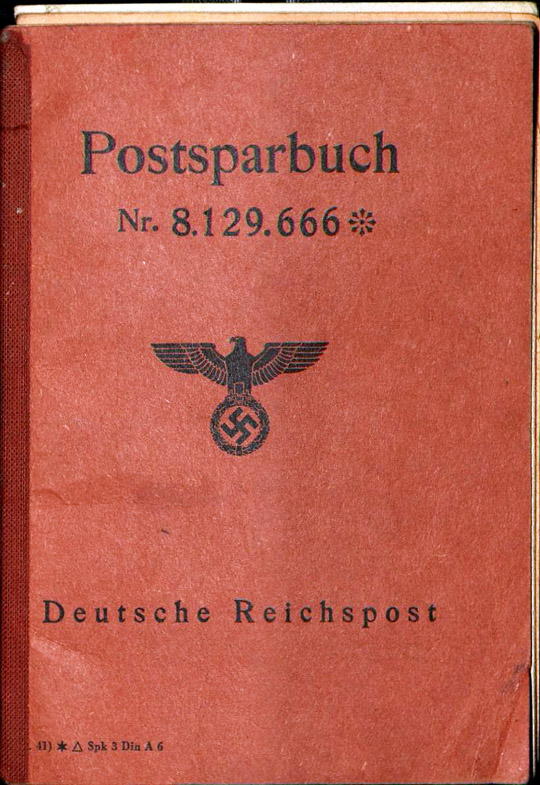

Hilde had no money to pay a lawyer: she had just one Reichsmark in her savings account with the German Postal Bank (Number 8.129.666). The attorney assigned by the court to be her public defender knew that the death penalty was a foregone conclusion even before the beginning of the trial and that an appeal against a sentence of the »Special Court« was not admissible.

The »Special Court« was a political instrument designed to impose rapid execution of the wartime regulations of the belligerent regime and was therefore part of its war crimes.

During the Nazi regime Austrian law was still applied, but mostly in connection with special war ordinances of the »Council of Ministers for Reich Defense« under Hermann Goering’s presidency – in particular with the »Regulation against enemies of the people« from September 5, 1939 that made »petty larceny« into a capital offense when attached to wartime ordinances § 1 »plundering« and § 4 »taking advantage of wartime conditions« – Paragraphs, which the Nazi regime, which exploited its occupied territories and conscripted forced laborers, used as an implement of terror on the »home front« – to »deter« crimes as it was said. The well-publicized execution of a victim would provide an example to deter others.

The »Reich’s defense« was powerless against the air raids on Salzburg, which had been branded as »terror bombing«. Instead of the powerful enemy, their retribution or revenge hit only the weakest on the »home front«: first two prisoners of war performing forced labor had been caught with two packs of cigarettes worth six Reich marks they had found in the ruins of the Salzburg main railway station.

For that »crime« the Salzburg Gestapo had the Russian Alexander ZIELONKA, whose clothing carried the stigma »OST« [East], hanged publically – a victim of political and racist persecution.

The Italian Arcangelo PESENTI who was guilty of the same »crime« was tried by the Salzburg »Special Court«, which sentenced him to death and he was executed in the Munich-Stadelheim prison.

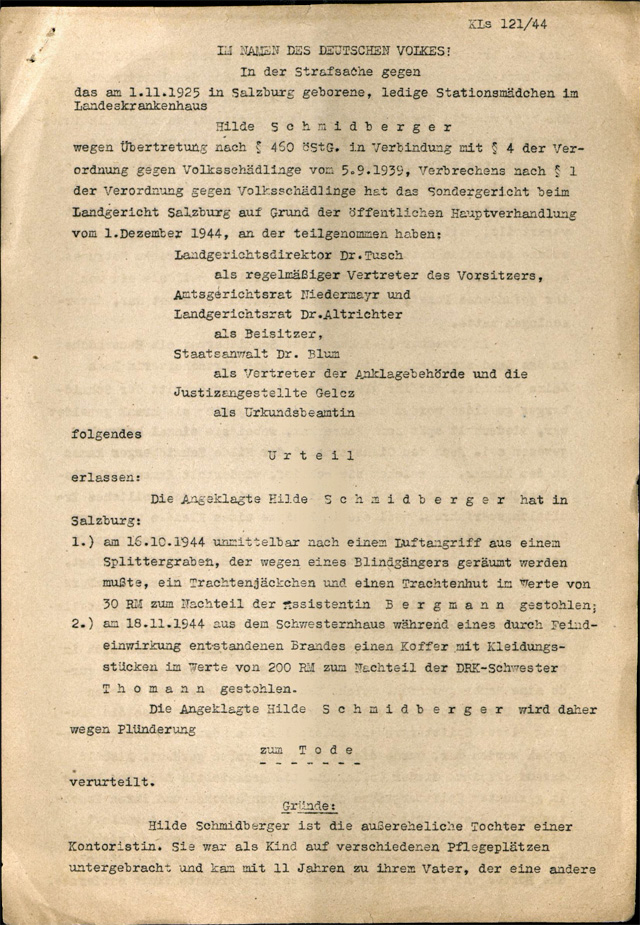

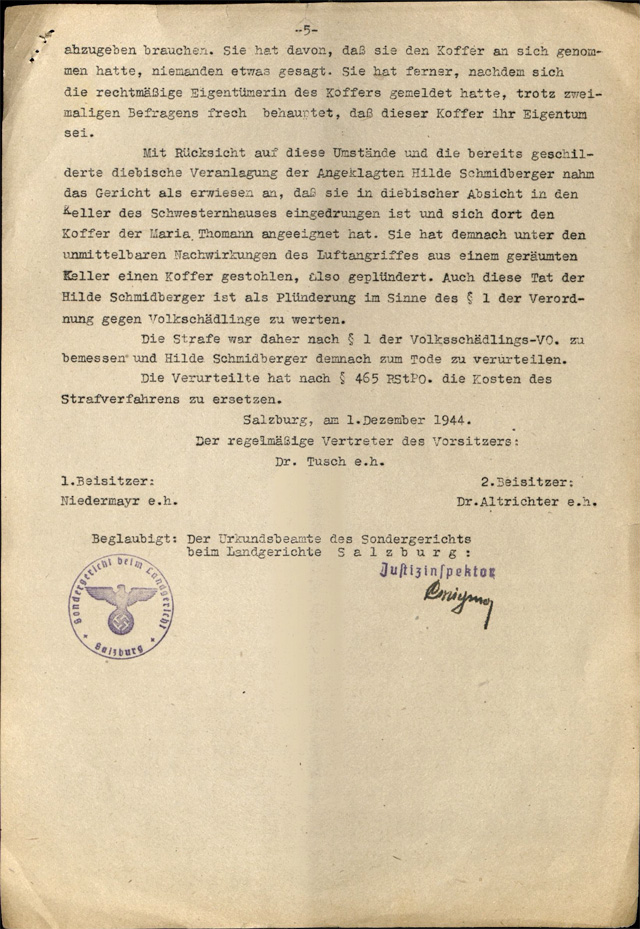

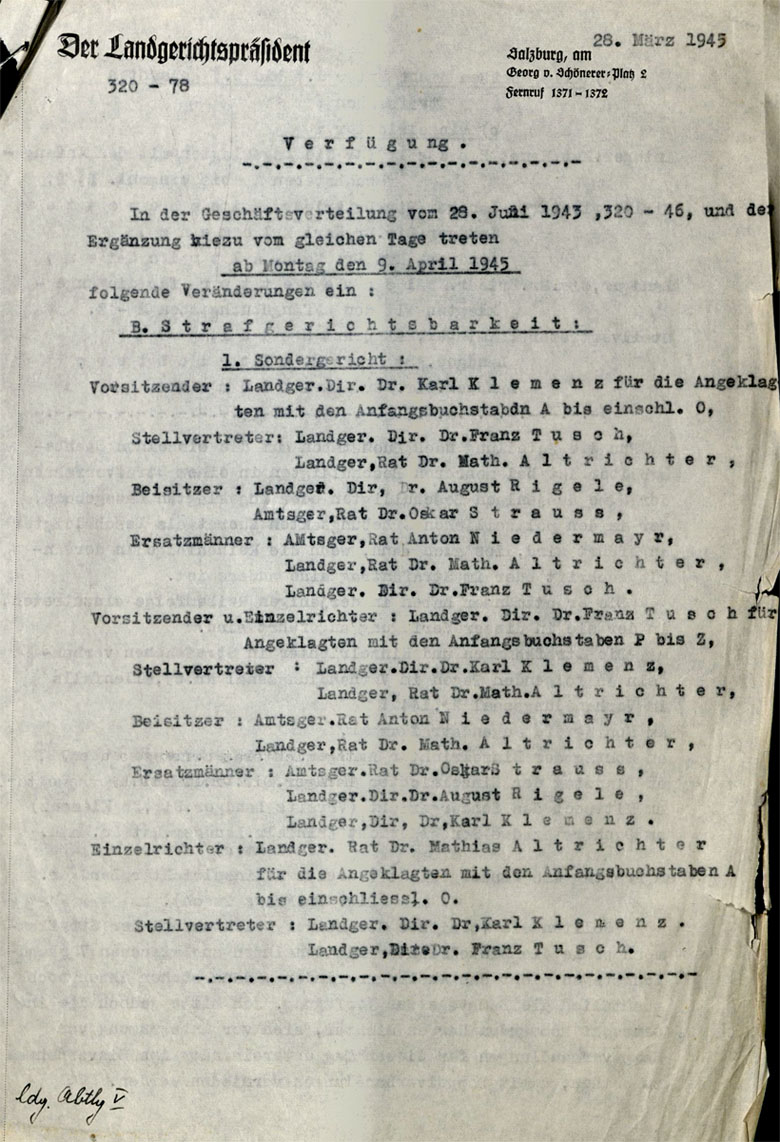

The criminal file for Hilde SCHMIDBERGER has the number KLs 121/44. It is clear that mostly Austrian jurists acted as judges of the »Special Court«, but with German official titles: »Landgerichtsdirektor« [State Court Director] Dr. Franz Tusch as Chairman, with »Landgerichtsrat« [State Court Councilor] Dr. Matthias Altrichter, and »Amtsgerichtsrat« [lower court counselor] Anton Niedermayr as fellow judges – all three were Nazi »old party comrades« from the early years of the Nazi movement and Nazi party functionaries, as well. Only the prosecutor Dr. Rolf Blum was a German lawyer and not an Austrian.

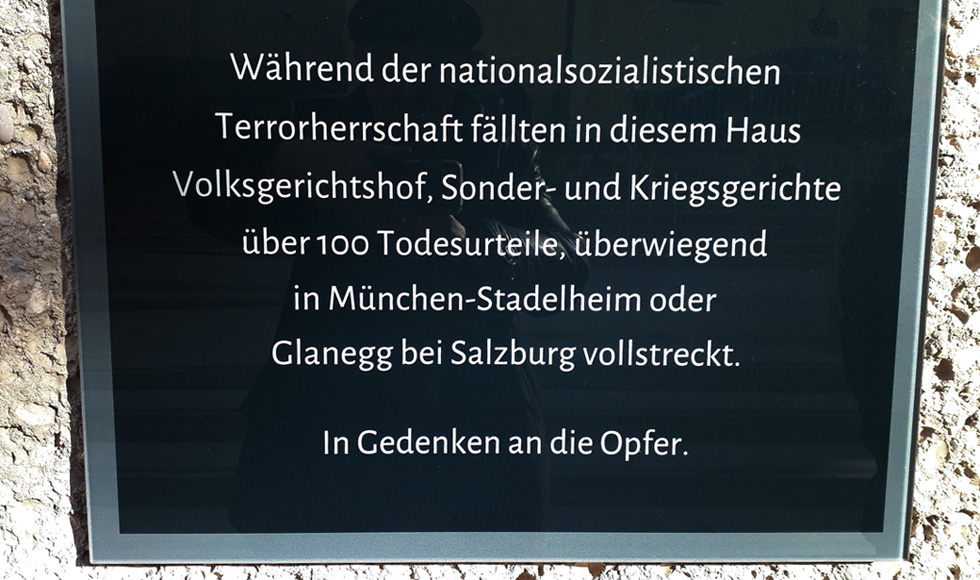

The trial took place in the felony court room of the Salzburg courthouse on the Rudolfsplatz, which the Nazis had renamed in honor of the prominent Austrian German-nationalist fraternity leader and Antisemitic propagandist Georg von Schönerer.

It was there on December 2, 1944 that the »Special Court«, after a two and a half hour long process, pronounced a death sentence »in the name of the German people« on 19 year old Hilde SCHMIDBERGER, as requested in the charge by SS-Sturmbannführer [Major] Dr. Balthasar as chief prosecutor.

Hilde’s father Gustav Bruzek, who was also persecuted by the Nazis, filed a request for mercy that was rejected out of hand. On December 5th his daughter was transferred from the Salzburg jail at Schanzlgasse 1 to the Munich-Stadelheim prison where she spent the last 57 days of her life in a death row cell.

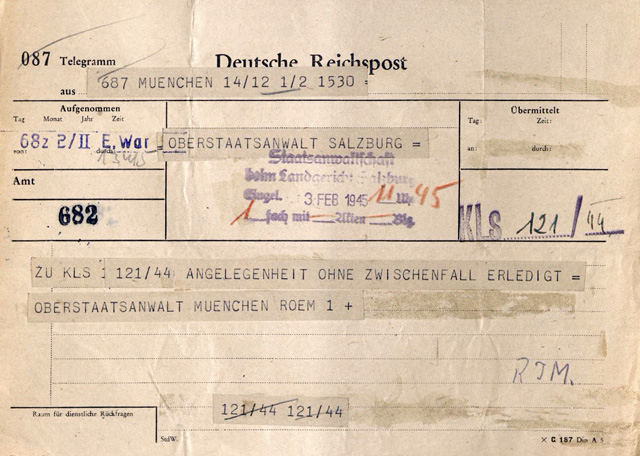

At around 4:19 pm on January 31, 1945 – four days after the liberation of the Auschwitz death camp – Hilde SCHMIDBERGER was decapitated in München by the guillotine of executioner Johann Reichhartt. At that point the Munich chief prosecutor sent his Salzburg colleague a telegram: »Matter settled without incident«.

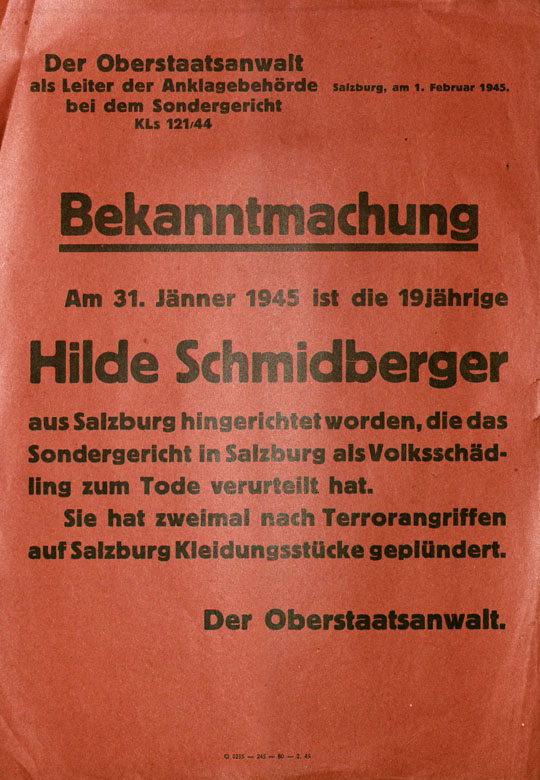

Survivors were prohibited from sending out obituaries. Instead 80 red posters were put up on public buildings and advertisement columns around the city of Salzburg: a »notice« from the leaders of the prosecution authorities of the Salzburg »Special Court«.

The legal perpetrators were kept anonymous, only the stigmatized name of their decapitated victim appeared on the posters: Hilde SCHMIDBERGER as »enemy of the people«. »Volksschädling«.

The young woman, who had been buried in the Perlacher Forest near the Munich prison, left her belongings to the prisoner’s care fund.

Since then, more than 70 years have passed and the Salzburg victim of injustice is now counted as politically persecuted in the electronic database of the Documentary Archive of the Austrian Resistance (DÖW). It is scarcely known, however, that the Austrian Revocation and Rehabilitation Act of December 1, 2009 retroactively cancelled »as non-existent all criminal judgments of the Nazi’s Special courts and tribunals«.

It is said that the persecution of war crimes began with the liberation when the perpetrators could be caught. There are 24 names on the »First Salzburg War Crime List«, published in June 1946, mostly Gestapo people, but no prosecutors and judges. Were they above suspicion?

In May 1945 the US occupation authorities closed all the courts in Salzburg and removed the judges from office who had held leading positions or been members of the Nazi party and its associations, including:

- the leader of the prosecution office, chief prosecutor Dr. Stephan Balthasar,

- the prosecutors Dr. Friedrich Blum, Dr. Ludwig Gandolfi, Anton Heim and Dr. Friedrich Stainer,

- the presiding judge of the Salzburg State Court Walter Lürzer,

- the judges Dr. Matthias Altrichter, Dr. Paul Kemptner, Dr. Karl Klemenz, Josef Hinterholzer, Anton Niedermayr, Dr. Julius Poth, Dr. Franz Tusch, Dr. August Rigele, Dr. Oskar Strauß and Dr. Ferdinand Voggenberger.

A few of the dismissed lawyers were interned for a while in the US prison camp Marcus W. Orr – known as the Glasenbach camp because the soldiers who guarded it were housed in the nearby Glasenbach barracks.

A few were not dismissed because they had already retired before 1945: for example Dr. Hans Meyer, who had presided over the »Special Court« from 1939 to 1943, and Oskar Sacher, who led the office for prosecuting cases of »race mixing« and served as co-judge on the »Special Court« until July 1943.

No lawyer was ever held responsible for any of the numerous death sentences: 71 in total, 26 under the leadership of Dr. Hans Meyer and 45 under the leaderships of Dr. Karl Klemenz and Dr. Franz Tusch. Nine judges served under their leadership as co-judges and also voted for the death sentences: Dr. Matthias Altrichter, Josef Hinterholzer, Walter Lürzer, Dr. Hubert Meder (died in 1945), Anton Niedermayr, Dr. Julius Poth, Dr. August Rigele, Oskar Sacher and Dr. Oskar Strauß.

As Chief prosecutor Dr. Balthasar was one of those most responsible for the death sentences – he had been a Nazi party member since 1933 and was an SS-Sturmbannführer. That led him to be categorized as a Nazi »offender«, but he was pardoned by Austrian President Karl Renner in 1950.

Most of the judges and prosecutors were classified as »minor offenders« and were cleared by the »lesser offender amnesty« of 1948. The younger ones among them were then able to resume their careers: for example Dr. Poth, Dr. Rigele, Dr. Tusch and Dr. Voggenberger returned as attorneys, Dr. Gandolfi became an administrative judge for the city and then a judge for courts in Salzburg and Linz.

Dr. Karl Klemenz, who had participated in at least 29 death sentences but who was never registered as a Nazi, had already been restored to a judgeship in 1947, although it was just for a district court in Leoben.

He made a political career in the »Association of Independents« which represented the interests of former Nazis and in 1949 he became a member of the Federal Council – the second chamber of the Austrian parliament [the less powerful equivalent of the U.S. Senate].

Dr. Matthias Altrichter, who had participated in at least 32 death sentences, was also classified as a »minor offender«. This was despite his Nazi party membership (May 1, 1938: Number. 6,347.572, and thus holder of one of the membership numbers reserved for »Old Party Comrades« [from 6,100.001 to 6,600.000]).

Worse still, Dr. Altrichter was classified as a »minor offender« despite his SA Stormtrooper and SS memberships (he was a Senior Squad Leader [Oberscharführer] in the SA and a patron member of the SS with membership number 1,403.697) [patron members were not active in the SS, but they made monthly contributions to it] and despite his leadership functions in the Nazi Regional Legal Office and the Nazi Legal Confederation.

Hardly had he been amnestied in 1948 when he again served as a judge, becoming a presiding judge and then President for the Salzburg State Court from 1958 to 1968 – for which service he was honored with the Large Silver Medal of Honor of the Austrian Republic, and the City of Salzburg ring of honor [State Capitol City Salzburg Gazette, May 15, 1969].

There was a long silence about one victim of Salzburg’s Nazi justice system: the high court justice Johann LANGER. LANGER had been »furloughed« when the Nazis took over in March 1938 and had put an end to his life in the Dachau Concentration Camp.

On August 28, 2008 a Stumbling Block was laid in front of his last Salzburg residence with the participation of Dr. Philipp Bauer, the vice-president of the Salzburg State Court.

On that occasion Dr. Bauer called for the further examination of the history of the Salzburg justice system under the Nazi regime and the personnel continuities after 1945.

That has begun.

Sources

- Salzburg Municipal Archives: Police registration files

- Salzburg State Archives: Case file KLs 121/44 of the Salzburg Special Court

- Documentary Archives of the Austrian Resistance (DÖW)

- Bavarian State Main Archives Munich: Execution file JVA Munich 666

Translation: Stan Nadel

Stumbling Stone

Laid 28.09.2017 at Salzburg, Rudolfsplatz 2

Hilde Schmidberger

Hilde Schmidberger

Hilde Schmidberger’s Savings Book, Contents: one Reichsmark

Hilde Schmidberger’s Savings Book, Contents: one Reichsmark

Death Sentence for Hilde Schmidberger

Death Sentence for Hilde Schmidberger

Death Sentence for Hilde Schmidberger

Death Sentence for Hilde Schmidberger

Telegram from the Munich Superior Prosecutor informing his Salzburg that the sentence had been carried out

Telegram from the Munich Superior Prosecutor informing his Salzburg that the sentence had been carried out

Poster notifying the public that Hilde Schmidberger had been executed

Poster notifying the public that Hilde Schmidberger had been executed

The judges of the Salzburg Special Court, 2 Georg-von-Schönerer-Platz

The judges of the Salzburg Special Court, 2 Georg-von-Schönerer-PlatzSource: Salzburg State Archives

The symbol of the Nazis' civil and military courts: A sword and scales of justice combined with the Nazi Party eagle and swastika

The symbol of the Nazis' civil and military courts: A sword and scales of justice combined with the Nazi Party eagle and swastika

Commemorative plaque at the Salzburg Provincial Court

Commemorative plaque at the Salzburg Provincial CourtPhoto: Gert Kerschbaumer

Photo: Gert Kerschbaumer

Photo: Gert Kerschbaumer