Berta SCHMIDBERGER survived the Holocaust as a six year old and she was 73 years old when Salzburg’s Mayor Heinz Schaden welcomed her to the start of the city’s »Life in Terror« lecture series on September 15, 2011.

Until then the public was unaware of the fact that in the last days of WWII, on February 14, 1945, five Salzburg women and two children were deported from the police jail on the Rudolfsplatz (which the Nazis had renamed after the notorious Austrian promoter of German nationalism and Antisemitism Georg von Schönerer), to the Theresienstadt concentration camp on »Special transport IV/15e«. They arrived there on February 15, 1945 and they were freed by Soviet troops on May 8, 1945.

The names of those liberated in Theresienstadt, including the 41 year old Friederike Schmidberger and her two children Berta and Stanislaus, six and nine years old respectively, can be found in the Theresientstadt Memorial Book – Austrian Jews [Theresienstädter Gedenkbuch – Österreichische Jüdinnen und Juden] published in 2005.

Despite being listed among the Jewish survivors, Friederike Schmidberger wasn’t Jewish – not even in the expansive terms of the Nuremberg Racial Laws. She had been born in the Salzburg community of Vigaun bei Hallein (a few miles south of the city of Salzburg) and been baptized Catholic.

She grew up under precarious circumstances as the child of an unmarried maid servant. Later she lived and worked in Hallein, Salzburg and Vienna – living an eventful life during which she never married, but in which she had a Jewish partner named Nathan Fogel.

Friederike Schmidberger had two children with her partner Nathan Fogel: Stanislaus, born on April 1, 1935; and Berta, born in Vienna on July 22, 1938.

Under the Nazi regime she lived in Salzburg and Hallein with her children while her partner Nathan Fogel was expelled to Poland in November 1938 and survived the terror years later during the Nazi occupation – separated ways and fates.

At the beginning of the Second World War Friederike Schmidberger went to occupied Poland in search of her expelled life partner Nathan Fogel – which turned out to be a futile and dangerous journey.

While she was gone Berta and Stanislaus were in the Salzburg city children’s shelter at 6 Bärengässchen.

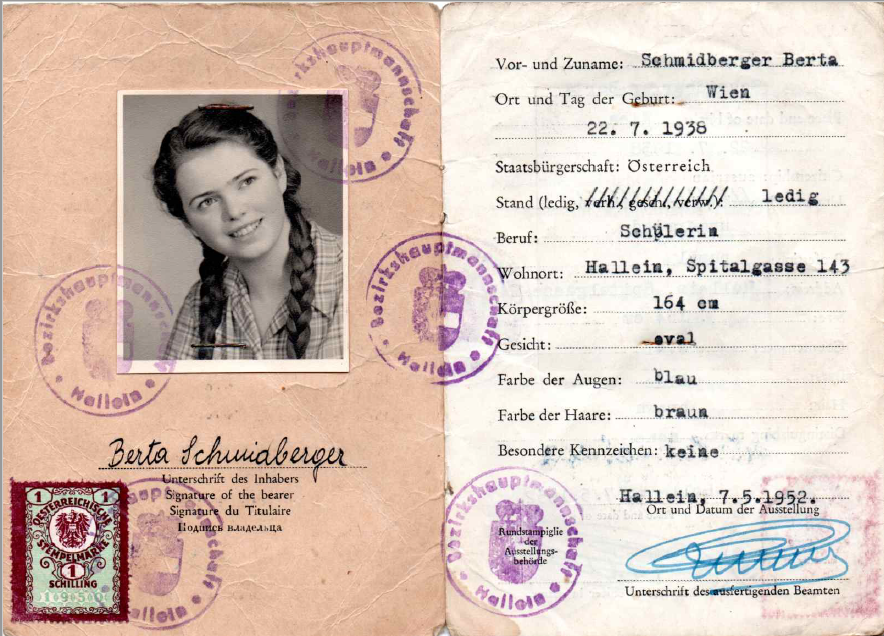

The two children were registered by police there and from their identity cards it is clear that their Jewish »descent« wasn’t known to the Gestapo or any other National Socialist authority.

However, when Ms. Schmidberger went to work in a reserve hospital in Hallein in 1943 and was registered there with her children, the authority responsible for illegitimate children became suspicious. They managed to establish the identity of the biological father of Berta and Stanislaus.

On October 1, 1943 the regional administration for Hallein notified the Salzburg Gestapo about the »ancestry« of the two children in the following terms:

It was subsequently determined that the above-mentioned minors are considered Jews on the basis of the first decree of the Reich Citizenship Law of November 14, 1935 (RGBl. I. S. 1333). The minors stem from a relationship between Fräulein Friederike Schmidberger and the Jew Nathan Vogel [Fogel], whose current whereabouts are unknown.

The Jew Nathan Vogel [Fogel] acknowledged his paternity of these children. Fräulein Schmidberger, who had been employed in the legal office of the Hallein reserve hospital, was dismissed without notice on August 11, 1943.

As a result the mother and her minor children have now become burdens on the public welfare. I ask you to arrange for their evacuation [deportation].

According to the cited decree of November 14, 1935 (§ 5 (2) (d)), a »Jewish half-breed« who came from extramarital relations with a Jew and was born after July 31, 1936, was considered a Jew.

The Hallein administration thus called for the implementation of a German law that only became valid for Austria after the »Anschluss« – an ex post facto unjust and arbitrary maneuver.

The siblings Berta and Stanislaus, who were members of no Jewish community and had no Jewish beliefs, suddenly counted as Jews and therefore – with the firing of their mother – were regarded as social cases who should be »evacuated« [deported], a phrasing that suggested that they were to be protected from a threat rather than sent to be persecutes – perfidy in the choice of words, calculation in the substance.

The mother and her vulnerable children led a life of fear and hope. In the sixteen wartime months until their deportation Friederike Schmidberger and her children had to report regularly to the Salzburg Gestapo.

Clearly the mother did everything possible to protect her children and that the Gestapo did not give the request of the Hallein administration for the »evacuation« of the two children any priority.

On March 7, 1944, five months after the notice from the Hallein administration to the Salzburg Gestapo office, the Gestapo Deputy Director Theodor Grafenberger wrote back:

The evacuation of the persons subsequently identified as Jews will be arranged at an appropriate time. Until then, the Jews are to remain in their previous place of residence.

As the Gestapo Salzburg did not order an »evacuation« of the two children in the following months – probably at the request of their mother – the Halleiner authority repeated its urgent request on 15 August 1944:

If possible, I ask you to carry out the evacuation of the two mentioned children as soon as possible, because the children’s mother cannot be supported by any authority.

In other words the claim of the authority in its letter to the Gestapo on October 1, 1943 that the dismissed mother and her children were a burden on the public purse was in fact a lie. The administration had rejected any social responsibility for the support of the unemployed mother and her two children and they were dependent on the mother’s helping in an inn and thanks to the help of dear friends, who risked being denounced as friends of the Jews.

The mother who refused to abandon her children in the time of their great danger deserves the greatest respect. But this does not explain why or how the mother, who was not Jewish, could travel to Theresienstadt in a »transport of Jews« – with the consent of the Gestapo. Friederike Schmidberger was not a person of many words, but rather a courageous mother who explained it with simple words in her handwritten CV:

At the beginning of January [February] 1945 the Gestapo came for my children, but because of my voluntary commitment to the Jewish community I was allowed to accompany my children.

The Gestapo delivered the mother and her two children to the police jail on the »Georg-von-Schönerer-Platz« [Rudolfsplatz], and after two days and nights twelve weeks before the liberation, on February 14, 1945 they were deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp.

Berta and Stanislaus survived the terror years thanks to the courage and care of their mother. In July 1945, after the end of a typhus epidemic and quarantine in liberated Theresienstadt, they were able to return to Salzburg with a US army military transport.

Documents indicate that they had been severely traumatized.

In 1948 Friederike Schmidberger and her two children applied for victims’ compensation at the offices of the Salzburg State government, but were only recognized as »victims of political persecution« at the end of 1952.

Nathan Fogel, Friederike’s partner and father of the two children survived the persecution in Poland and returned to Salzburg in September 1946.

In the mid-1950s they all moved to Leopoldsdorf in the Marchfeld of Lower Austria, and then finally to Vienna. But there was no happy ending: the father died young from a heart attack, then the mother from a stroke – and as they were still unmarried and of different religions they were not buried together.

In 1991 Stanislaus died at age 56, he was the last person who shared his sister Berta’s painful memories.

Berta SCHMIDBERGER, was an honorary member of the Austrian Federal Association of Jewish Communities as a Holocaust-survivor.

She died on October 29, 2015 in Vienna at age 77 and was buried beside her mother and her brother Stanislaus.

Sources

- Salzburg city and state archives

- Hallein city archives

- Municipality of the city of Vienna

- Vienna Jewish Community

- Private archive of Berta Schmidberger

Translation: Stan Nadel

Stumbling Stone

Laid 04.08.2018 at Salzburg, Rudolfsplatz 3

Identity Card of Berta Schmidberger

Identity Card of Berta SchmidbergerPhoto: private collection

Berta Schmidberger and Mayor Heinz Schaden on September 15, 2011

Berta Schmidberger and Mayor Heinz Schaden on September 15, 2011Photo: Salzburg City Archives

Grave of Friederike Schmidberger and her children Berta & Stanislaus in the Vienna Central Cemetery

Grave of Friederike Schmidberger and her children Berta & Stanislaus in the Vienna Central CemeteryPhoto: Esche Schörghofer

Photo: Gert Kerschbaumer

Photo: Gert Kerschbaumer